Painting The Syrian Tragedy

THE SHARP distinction between good and evil is made manifestly clear in a swirling image of two halves, one bright and one dark. From the darkness, snarling monsters emerge, baring their teeth, and shadowed by ghoulish men of war, all of them threatening to pour into the bright side of the canvas, where some of the buildings and monuments of Western Europe are clearly visible – among them St Peter’s Basilica, the Brandenburg Gate, and the Eiffel Tower. The forces of darkness are held back by the central figure of a woman – perhaps the Virgin Mary – bearing a sword, while beneath her is depicted a tide of refugees fleeing the horror of war for the sanctuary of peace.

Such imagery would surely speak volumes to the millions of Europeans shocked and terrified by the Islamist terrorist attacks that have proliferated across the continent in the last two years with massacres in Paris, London, Berlin, Nice, Brussels, Manchester, Stockholm and Barcelona. Yet this painting, called Darkness March, is more prophetic than retrospective as it was painted some five years ago during the Siege of Homs in the Syrian War, at a time when many Europeans might have felt rather safer than they do today, when the ‘war on terror’ seemed to be waged largely in faraway places.

A Syriac Christian

The painting is the work of Farid Georges, a Syriac Christian from Homs who has depicted the six-year war in his native country in some 25 paintings in total. The painting was also among 11 works inspired by the war shown in Catholic cathedrals of north west England and Wales recently in an exhibition called Portraits of Faith: Syria’s Christians Search for Peace, organised by Aid to the Church in Need, the Catholic charity.

Other images in the collection are just as evocative. One of them, called The Explosion, was painted after Farid witnessed an attack in Homs which left dozens of civilians either killed or injured.

In this painting a huge plume of grey smoke billows into a vivid blue sky as rooftops and buildings buckle into twisted iron and debris and then begin to fall. Beneath the smoke, human wreckage of the blast is visible: faces of victims contorted in pain, and others dead, lying in pools of their own blood.

“This was particularly painful to paint because I witnessed the explosion” said Farid. “I saw the smoke rising and knew there had been an explosion, and when I eventually went to the scene I was confronted with the scale of the damage, the destruction that had happened, and the sheer number of casualties, people who had perished of all different ages.”

Farid Georges explained that to this day he does not know the source of the attack. “I don’t care to know,” he said, adding, “At the end of the day every faction will blame it on the other one; you will have all these different stories, narratives of what happened and who caused it. I don’t care about that. What I care about is that this sort of thing shouldn’t happen anywhere. That is what matters to me.”

Surreal touch

Farid has always been an artist, but he has not always painted war. Yet the corpus of war art he is creating, however, might one day distinguish him as one of the great war artists of his generation. Born in 1946 at Ain Albarde, Syria, Farid trained at Fine Arts Institute in Homs from 1968 before joining the Fine Arts Academy in Rome eight years later.

Before the war, he had shown his work at exhibitions throughout Italy, including galleries in Rome, Florence, Venzone, Siena, Crotone and Sicily. He has also exhibited extensively throughout the Middle East.

Farid was living in Homs when the city suddenly became one of the bloodiest theatres of the war, and he painted as fighting engulfed residential areas. Eventually, he and his family fled into the countryside, and spent a year there before finally leaving Syria for the safety of other countries.

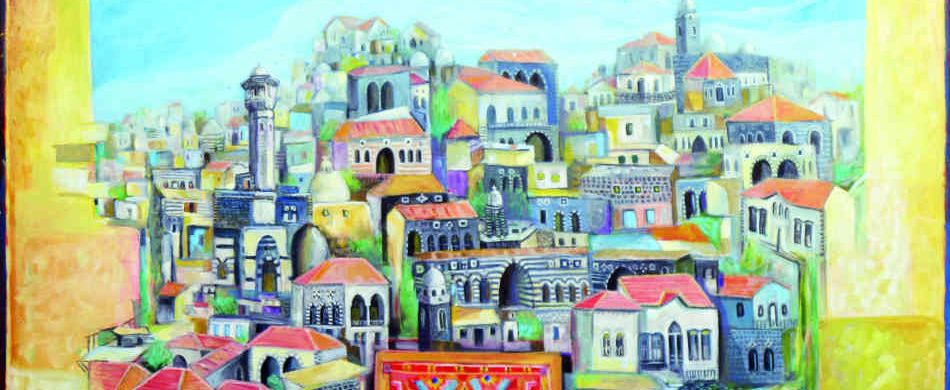

Most of his war art spans the period between 2012 and 2014. Described by Farid as realist with a “touch of surreal fantasy” in style, it tells a story like a book. An early painting, called the Flower of Homs, shows the city at peace before the violence, for instance. It is in a bright, slightly modernist style, and like others is perhaps comparable in character to the 20th century works of Marc Chagall, the French modernist.

Then, as the paintings progress to the horror of war, some people may perhaps be reminded of the works of Francisco Goya and Pablo Picasso, with the images darkening and dismembered bodies filling up the canvasses as the people and their dwellings are destroyed. “I have known many, many people who have been killed in Homs,” says Farid.

Reconciliation & healing

Finally, his images evoke the hope of peace, reconciliation and healing. This is evident in Forgiveness in Ma’aloula, one of the later paintings which begin to point beyond the war. It depicts an enormous figure of Christ standing astride two hills representing the ancient Syrian village where Aramaic, the language of Jesus, was still spoken. The hills form faces staring at each other. Farid said, “It (Ma’aloula) was invaded, the people were displaced, the churches were destroyed. To me, the people who did that do not represent Islam because Muslims have lived there together with Christians for a very long time.

“In Ma’aloula there are these two mountains and a small valley between them. I painted Jesus standing in the middle, first of all separating them so there wouldn’t be any more fighting but then bringing them together to reconcile them because these people, representing Islam and Christianity, belong together.”

Father van der Lugt

Besides Jesus, another symbol of peace for Farid was his friend, Fr. Frans van der Lugt, the Dutch Jesuit shot in the head in Homs in 2014 by assassins after he refused to abandon the poor and homeless of the city. Farid said he was “very shocked and saddened” by the priest’s murder. “I knew him very well; we had a very close relationship,” he recalls. “He has quite a legacy in Homs. He was a Jesuit Christian, but he treated all the people of Homs as equals. Even if they were Muslims, they were all his children. His monastery at Homs had Muslims and Christians in it all the time. He would give them refuge there and feed them until all the food in the monastery had run out.”

Farid painted scenes from the life of the priest as a tribute to him. It now hangs in Farid’s home in Nuremberg, Germany, where he has lived with his wife and two daughters since 2015. He continues to paint the war from his studio in Germany. Today, however, most of his war art depicts hope rather than suffering. Indeed, one day he expects to return to Syria.

Sharing pain

Painting the war is, for Farid, telling the story of his own life and that of his benighted country, but it also gives him the opportunity to speak to people around the world about the suffering that so many Syrians have endured. He said that he hoped people, on viewing his works, “will first of all be more aware so that they will learn more about the Syrian people and what is going on, and that they will feel the injustice these people have suffered, and that they will help in any way possible”.

His exhibitions of war art were like a “cry for help,” Farid explains. “Material help is only one part of the help people can give,” he says. “What is more important to me is that they feel the pain. So the help can be spiritual in nature; it can be just partaking in the pain, sharing the pain. If that results in humanitarian aid that’s fine, but it is more about the all-encompassing sharing of the pain and suffering.”

“The Syrian people are now scattered all over the world; they are everywhere as refugees,” he continues. “It is necessary to understand these refugees and to help them to go back home. That is what so many of them want to do; they want to go back home and live in peace as they have always done. In Syria there was such a level of destruction, with so many atrocities committed, that there is barely much else that can happen. The normal thing now is for people to come back to their senses, so I believe that peace is not very far away… peace is within sight… I am hopeful that there will be peace again in Syria.

“I wish and hope that it will return to the diverse mosaic of peaceful coexistence that we have. We have more than 20 sects of different confessions in Syria. We have always lived in peace and coexistence. All we need is for us to be left to our own devices. We just have to be left alone. We don’t need anyone to meddle in our affairs, any external interventions. If they would only leave us alone we know how to live together.”

Sense of change

Peace is indeed slowly returning to Syria. Most of the fighting is in the east of the country where both the Russians and the Americans are helping to destroy the remnants of ISIS. In the west, isolated attacks continue, such as the rocket attack on the International Trade Fair in Damascus in August, but generally Syrians sense change and are beginning to return to the land they love, including the Christians of Homs and Aleppo who are now busily rebuilding homes and shops.

It would be wonderful to imagine that Farid might one day conclude his art with a celebration of peace in Syria. That day may well come. For Europe, however, Darkness March perhaps presents an image of another conflict which is likely to be for more enduring.