Effective Preacher

THAT unexpected evening sermon in Forlì, in the late summer of 1222, marked the beginning of a radical change in Anthony’s life. As his particular vocation for preaching began to emerge in the 27th year of his life, our Saint emerged from the obscurity of history. His situation could be summed up with one image in particular: for years he had been playing the ‘piano of sermons’ for his brethren and himself. During the long tormented hours of practice on that ‘piano’, his fingers had not always done what he had wanted them to do. Despite his constant study of the score, he had never managed to find the right note: what he played did not seem to match what had been written, giving rise to boredom and frequent outbursts of impatience.

Then, all of a sudden, one fine day the monotonous clutter took on an unusual tone. His brethren looked up from their books and exclaimed, “Who would have thought of that!” The key to the kingdom of effective sermon-giving in all its nuances had clicked. If one wanted to visualise a common denominator or image for Anthony’s life up until 1222, then this could be it.

Three phases

Now the real concerts finally began. The years that followed, the few that were left for Anthony, were fully marked by his preaching activities. Experts on St. Anthony divide this short decade into three great periods, which followed one after the other. The first phase of his preaching activities in northern Italy lasted from 1222 to 1224; this phase began immediately after that memorable sermon in Forlì.

This was followed by the second period, from 1224 to 1227, which saw Anthony active in southern France. His final period of activity ended with his death in 1231, and saw him an ardent preacher once again in northern Italy. Even if on that evening in Forlì Anthony could not possibly have imagined, nor foreseen, all this activity and the fact that his ‘life calendar’ would be fully booked to the end, it would not have taken him long to notice the new speed and pace his life had taken on.

Francis’ revelation

However, if one takes a closer look, this new beginning in Anthony’s life was actually not so new. It had been heralded by the discovery of St. Francis and his followers. In the course of his long search for the right way of living, an episode in Francis' life forced himself upon him. It was in 1209 (probably on February 24, the Feast Day of Saint Matthias the Apostle) when Francis was attending a Mass service in which he heard a certain passage from Chapter 9 of Luke’s Gospel: “Jesus summoned the Twelve and gave them power and authority over all demons and to cure diseases, and he sent them to proclaim the kingdom of God and to heal the sick. He said to them, ‘Take nothing for the journey, neither walking stick, nor sack, nor food, nor money, and let no one take a second tunic. Whatever house you enter, stay there and leave from there. And as for those who do not welcome you, when you leave that town, shake the dust from your feet in testimony against them.” To this Matthew adds in 10:12-13, “As you enter a house, wish it peace. If the house is worthy, let your peace come upon it; if not let your peace return to you.”

Although Francis had heard these passages before, this time he had a sudden revelation, and said to himself, “This is what I want! This is what I am looking for! This is what I desire to do with all my heart!” The Poor Man of Assisi had understood what the Lord wanted from him, and within barely twenty years a rapidly growing movement had been formed.

Rolling avalanche

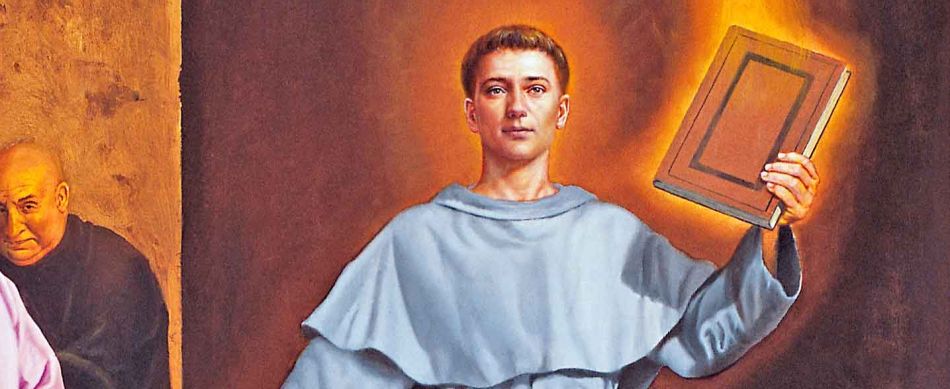

The Franciscan movement attracted so many people that it soon turned into a rolling avalanche, and Anthony became one of these many friars who was fascinated by this way of life. However, among the many Franciscan friars he was to become the one who discovered the right tone in which to make the transmission of the Gospel not only feasible, but also appealing to the people of his times. These wandering preachers, simple, poor and homeless, went to the people – they did not wait for the people to come to them. Their sermons were not delivered in the distant Latin language which ordinary people could only identify as bookish and incomprehensible; the vital secret of their success was that their sermons were delivered in the language spoken by the simple, uneducated audience, who were thus able to understand in a vivid way.

This circle of friars spread all over Europe in no time: one group, under the leadership of friar Pazifikus, a poet, was sent to France. Another group, under the guidance of Caesar of Speyer, undertook the arduous journey over the Alps to Germany. A third group, led by friar Agnellus of Pisa, went over to England, as described by friar Thomas of Eccleston in his chronicle.

Penitence and peace

Some further comments, however, should be made about the nature of their sermons. They were mainly sermons of penance and peace, simple and short as Francis demanded in his Rule. He also asked that the friars who proved capable of preaching be officially promoted by their Superiors to the office of preacher. This would have happened to Anthony shortly after his successful preaching in Forlì, and it can only be assumed that it was friar Gratian who first promoted him to that office before Anthony received official approval from Francis himself.

But what was Anthony’s ministry like? From now on we only hear about Anthony’s main task of preaching, interrupted at times by the teaching of theology, and so naturally the question arises: what were his sermons like? How did he convey his theological knowledge and the fruit of his contemplation and meditation to his audience? Of course, we have no video recordings, only a few brief descriptions.

The art of the sermon

A sermon is not just a list of enlightening, profound and moving thoughts. There’s much more to it: it also consists of gestures, word choice, tone of voice, facial expression, posture; all this decides quite substantially whether it will be successful or not.

We cannot even reconstruct the precise words Anthony used in his sermons to the crowds. His sermon notes that have been handed down to us (collected in English in four volumes) have very little to do with the actual content of his preaching and the words he used. Most of these writings are drafts of sermons which, moreover, were written by our Saint in Latin. They were also written in the form of a textbook for future Franciscan preachers, whereas his actual sermons before the crowds were delivered in the local dialects.

Repentance and light

In conclusion, a few more indications from the Assidua describing what happened after the famous sermon in Forlì might be helpful, even though that biography does not hand down any of the sermon’s content to us. The Assidua tells us that Anthony threw himself into his new role and duties with great energy and enthusiasm. He restlessly rushed from one place to another, and this is how we should imagine him for most of his remaining years. And almost immediately, Anthony felt at ease in discussions with heretics, proponents of erroneous doctrines and other groups with a grudge against the Church. Accounts of his actions constantly emphasize that the effects of his sermons were always the same: they produced repentance, enlightened those who had strayed and encouraged them along the right path.