Bible Expert

THERE ARE many images – too many to count – of Saint Anthony with the Bible in his hand, depicting him as ‘Doctor of the Church’ or ‘Evangelical Doctor’; the title was bestowed upon him long after his death by Pope Pius XII on January 16, 1946).

The history behind these titles goes way back to Anthony’s childhood, thus, long before he took the decision to follow the Franciscans. It is a fortunate circumstance that Anthony was already deeply steeped in the knowledge of the Bible before his entrance into the Franciscan Order because, at least in their beginnings, the Franciscans belonged to those Orders which had not cultivated theological and biblical studies. The 10th chapter of the Rule of the Franciscan Order, confirmed by Pope Honorius on November 29, 1223, is titled: On the Admonition and Correction of Brothers. The chapter goes on to say, “I admonish and exhort the brothers in the Lord Jesus Christ to beware of all pride, vainglory, envy, avarice, worldly care and concern, criticism and complaint. And I admonish the illiterate not to worry about studying, but to realize instead that above all they should wish to have the spirit of the Lord working within them, and that they should pray to him constantly with a pure heart, be humble, be patient in persecution and infirmity, and love those who persecute, blame or accuse us…”

At first glance, this statement would seem to be an attack against knowledge; however, one must remember that the knowledge, the science, of those times was theology. What in reality Francis was trying to do was impress upon his followers the most fundamental aspect of their belief: a faithful and humble approach to God on a path of peace towards our brothers and sisters.

However, such guidelines could become an obstacle for someone who had not benefited from an education, and who wanted to join the Franciscan Order without knowing much about the Bible.

Saint Anthony himself genuinely seemed to subscribe to the same message. Yet, it turned out to be a great source of help that Anthony had already gained his knowledge of the Holy Scriptures before he decided to join the Franciscan Order.

A saint at school

The Assidua describes Anthony’s life in a plain and straightforward manner. The author covers the whole of the first part of the Saint’s life in very few lines.

“Indeed, they [Anthony’s parents] entrusted him to this church [Lisbon’s Cathedral], dedicated to the holy Mother of God, so that he learn the sacred writings there, and, as if led by a presentiment, they confided the future herald of Christ to the education of Christ’s ministers.”

Anthony was therefore educated by “Christ’s ministers” right next door to his parents’ home in Lisbon; and these “ministers” were the clergy and the teachers at the Cathedral school. This choice on the part of his parents determined exactly what kind of studies Anthony undertook: on the “sacred writings.” In essence, this consisted in the books of the Bible and the most important writings on the tradition of the Church, for example those of the Church Fathers.

Such a beginning should also remind us of the son of a citizen of Assisi who himself had recently become wealthy, Francis Bernardone, who had likewise received his education at the Church of Saint George in Assisi. And the contents of Francis’ lessons were also clear cut: the Latin edition of the Bible and, above all, the Psalms, were the instruments through which Francis learned to read and write. Francis would never forget these first lessons and their contents. From there on Francis developed his knowledge of the Holy Scriptures. A very similar process occurred in Anthony’s life.

Powerful memory

A few years later, when Anthony was about 16 or 17 years old, he found himself in the process of becoming a regular canon in the Augustinian community of Coimbra. He had already passed on from the novitiate in this community. The Assidua has the following to say in this regard: “He [Anthony] always cultivated his innate talents with special eagerness and exercised his mind with meditation. Day and night, whenever the occasion arose, he would not neglect to read the Scriptures. In reading the Bible with attention to its historical truth, he also strengthened his faith with allegorical comparisons; and, in applying the words of the Scriptures to himself, he edified his affections with virtues.”

His positive thirst for knowledge allowed him to explore the hidden meanings of the holy words, thus equipping himself with the means to protect his spirit in the face of the dangers involved in taking a false step. To reinforce this purpose, he extended his knowledge of the saints through research; and everything he read, he entrusted to his incredible memory. His memory was such that within no time he was able to show a depth of knowledge of the Bible that few people in his time possessed.

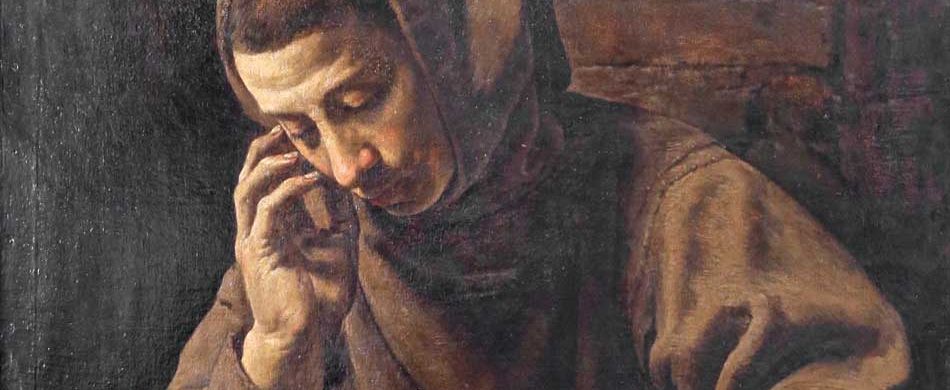

This font, from which he would later draw so creatively as a preacher and a teacher, was created slowly and with great dedication. It is easy to picture him under candlelight late at night in his monastery cell bent over the Bible with red eyes. He inhaled its contents; he lived and breathed the Holy Scriptures through all the heavy tomes and folios in which the Christian and theological tradition found its expression.

All these details he kept inside his head. It was sufficient for him to read them once or twice, and then he would never forget what had passed before his eyes. What he learnt at that time, he learnt ‘by heart’. Learning by heart is more than a mechanical process and, in Saint Anthony’s case, his phenomenal memory was not simply a database. What he read and learnt changed him radically; it moved and transformed him.

Anthony’s forefather

It may well be that the eager and still very young Bible student, Anthony of Padua, came across the following sentences in the course of his studies: “I interpret as I should, following the command of Christ: ‘Search the Scriptures’, and ‘Seek and you shall find’. Christ will not say to me what he said to the Jews, ‘You erred, not knowing the Scriptures and not knowing the power of God.’ For if, as Paul says, ‘Christ is the power of God and the wisdom of God’, and if the man who does not know Scripture does not know the power and wisdom of God, then ignorance of Scripture is ignorance of Christ.”

The author of the above words goes straight to the heart of the matter: “…ignorance of Scripture is ignorance of Christ.” This was Saint Jerome (347-420) in the foreword to his commentary of the Book of the Prophet Isaiah. One of the earliest and greatest experts and translators of the Holy Scriptures, Jerome’s works are part of the classics of Christian tradition, and were often the most important sources for a young man like Anthony, who was learning to read and write.

Evangelical Doctor

These are the general outlines of the background from which a future ‘Evangelical Doctor’ would emerge. To translate the significance of this to our period, we should take a look at paragraph 21 of the Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation Dei Verbum promulgated by Saint Pope Paul VI in 1965, towards the end of the Second Vatican Council. It states, “The Church has always venerated the divine Scriptures just as she venerates the body of the Lord, since, especially in the sacred liturgy, she unceasingly receives and offers to the faithful the bread of life from the table both of God’s word and of Christ’s body.”

Saint Anthony was to take a large bite of this Bread; he would reflect upon it and then pass it on to others through his sermons and the example of his life.

In my opinion, this could also be a task we give ourselves. No doubt, we do not have the vast and formidable memory with which Anthony was graced; we will not be able to pick up on each word as he did. Yet Saint Jerome’s sentence is in itself a sufficient task and a challenge to face up to in the footsteps of Saint Anthony of Padua, the Bible expert: Ignorance of Scripture is ignorance of Christ.

DOCTOR OF THE CHURCH

In 1996, in commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the granting of the title Doctor of the Church to St. Anthony, Pope Saint John Paul II wrote, “An intense cultural, theological and biblical formation helped the first lecturer of theology in the Seraphic Order to spend his life assiduously searching for God. He was nourished by an intense piety and an insatiable yearning for contemplation. In this process Sacred Scripture, constantly meditated upon in the rhythm marked by the Church’s liturgy, became the primary source of knowledge for his theology.”