May Insects

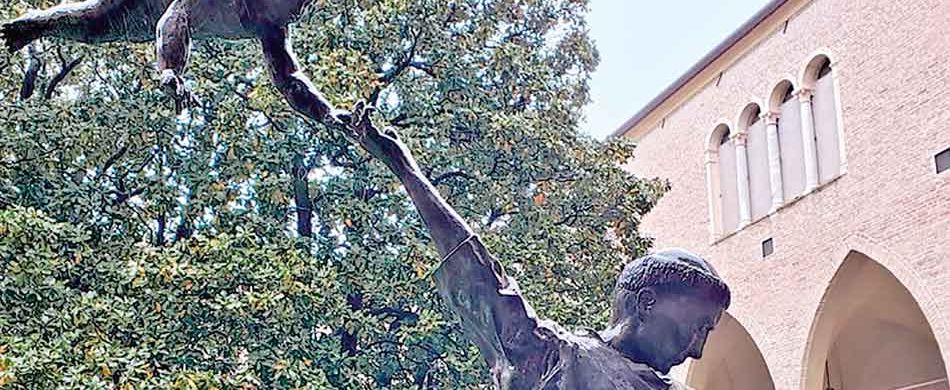

APRIL showers bring May flowers, it’s true, but they also bring May insects. Saint Anthony must have liked May because its many varieties of insects inspired a host of preaching ideas.

Anthony had a reputation for being a forceful preacher who earned the nickname “The Hammer of Heretics.” Nevertheless, in hearing confessions, and God alone knows how many they were, he was renowned for his gentleness and mercy. The Saint advised all preachers to act as he did, but without pointing to himself as an example. Instead, he illustrated his message by referring to a common woodworm.

The preacher

Woodworms feed on wood in the larval (worm) stage, which can last up to three years, depending on the species. The larva molts into a beetle which exits the wood through the holes and tunnels which it, as a larva, chewed. The various species emerge from their pupal case as beetles between April and August. By then, they have done their often considerable damage to both soft and hardwoods, not only in forests but also in homes, attacking shutters, furniture, and wooden walls. They betray their presence by the sawdust left behind and by their tunnels visible in the wood.

A preacher, Anthony noted, should “be the ‘most tender little worm of the wood’: a little worm that pieces and gnaws away the wood of the hard and unfruitful; ‘tender,’ that is patient and merciful towards the humble and contrite” (Sermons for Sundays and Festivals II, p. 78-79; translated by Paul Spilsbury, Edizioni Messaggero).

Anthony not only knew about these worms, but he must have picked a few of them out of the wood in which they were hiding, for he goes on to say, “Alternatively, just as there is nothing harder than a worm when it gnaws, but nothing softer when it is handled, so the preacher who sets forth the word of God should strike the hearts of his hearers hard; but if he is struck by insults, he should be gentle and friendly” (Sermons II, p. 78-79).

Anthony definitely was forceful in striking the hearts of his audiences, as attested by the attempts on his life by usurers whose consciences were pricked by Anthony’s pointed illustrations.

Dung beetles

In one of his sermon notes, Anthony compares usurers to dung beetles. Dung beetles come in various colors and sizes, but they have one trait in common: they all feed on feces. The “tunnelers” bury the dung wherever they find it. The “dwellers” live in the dung wherever it drops. The “rollers” roll dung into round balls which they use as a moveable food source and also as a breeding chamber.

Anthony used the “rollers” as an object lesson in a sermon about usury and greed. He begins, “The avaricious and usurious… pay no attention to the state of their life, its entry and its exit. In its entrance, there is no purse or penny, at its exit only straw and sack-cloth. They are naked as they enter, and they leave wrapped in a short shroud. Where do they get all their possession from? From robbery and fraud” (Sermons IV, p. 22).

Now that he has the audience squirming, Anthony introduces a verse from Habakkuk (2.6). “Woe to him that heapeth together that which is not his own.” Then Anthony adds his interpretation. “He is like the dung-beetle, which gathers much dung and with great labor makes a round ball; but in the end a passing ass steps on both beetle and ball, and in a moment destroys it and all it labored so long over. In the same way the miser or usurer gathers long the dung of money, and labors long; but when he least expects it, the devil chokes him. And so he gives his soul to the demons, his flesh to worms, and his money to his family” (Sermons IV, p. 22). This last sentence summarizes Saint Francis’ ending paragraphs in his first and second Letters to All the Faithful (Exhortations to the Brothers and Sisters of Penance). The friars must have frequently preached on this theme, by first calling the people to repentance and then reminding them that “you can’t take it with you.”

Wax moths

People could avoid being obsessed with the world if they put more time into contemplating their lives, their occupations, and their final end. However, this pleasant and necessary part of the spiritual life, sweet as honey, is not without danger. Anthony explains. “Natural History tells that spiders reproduce in honey-comb, and corrupt what is in the comb. Little worms are produced in the hives of bees, and they get little wings and fly” (Sermons III, p. 41).These “little worms” emerge from their pupa stage as wax moths, grayish insects about half an inch in length.

Wax moths attract spiders to live in honeycombs. “The spider weaves its web in the air” to snare these moths. Anthony applies this ecosystem to the spiritual life. “The spider of poisonous pride reproduces in temporal delight, and it spreads its web in the air, as it walks in wonderful things above itself. The worms of gluttony and lust are produced, which makes a man fly to the desire of what is not his. No wonder if, with such a mixture, the balm of contemplative life, or of pure conscience, is adulterated!” (Sermons III, p. 41).

Remedy for pride

What is the remedy for the pride that can poison the spiritual life? “You will prove yourself to be without the honey of transitory sweetness,” Anthony writes, “if you are… set in the spirit of poverty… of the Lord’s Incarnation” (Sermons III, p. 41).

Meditation on the Incarnation might yield a reflection such as this one: “Let the heavens be rent, let the Word come down, from whose face the pride of the mountains will melt away. ‘From your face,’ the presence of your humanity, the mountains would melt away. Who can be so proud, arrogant, and puffed up, if he attends closely to majesty emptied, power made weak and wisdom crying like a child? Is it not his heart that melts, like wax in the face of fire? And who will say with the prophet, In thy truth (in thy humbled Son, O Father) thou has humbled me?” (Sermons III, p. 285).

Who but Saint Anthony could open hearts to conversion by referring to woodworms, dung beetles, spiders, and wax moths?