Fighting the Culture of Death

IN THE LATE 1970s a brilliant young doctor from Amsterdam set out on what promised to be a long and distinguished career when he landed his first job at the city’s prestigious university hospital. In the event, he left medicine after just 18 months after he discerned a vocation as a Catholic priest, and entered the seminary of Rolduc in Kerkrade. Had he persisted in medicine it would be safe to surmise that within 30 years it is likely that he would have encountered a request from at least one of his patients to die by euthanasia, a request for him not to heal, but to actively kill a person by lethal injection.

Shrewd choice

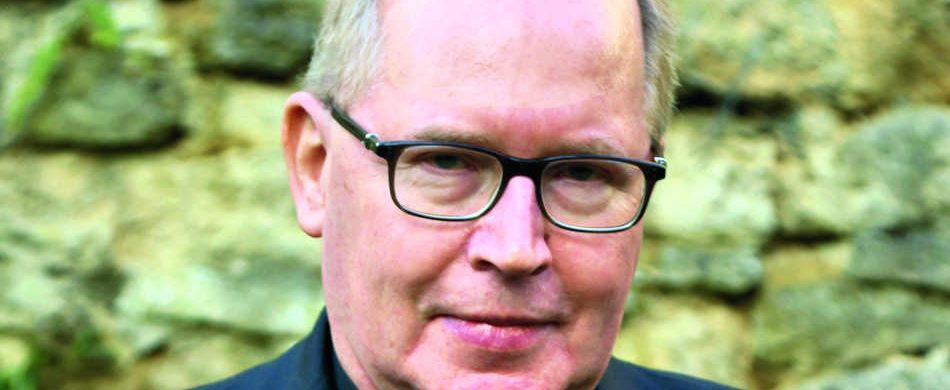

The former doctor is today Cardinal Willem Eijk, Archbishop of Utrecht and 70th successor to St. Willibrord, the English missionary under whose light the people of the Netherlands first received the Christian faith.

Willem Eijk was made cardinal in 2012 by Pope Benedict XVI, who must have recognized, quite shrewdly, that there was no man better suited to such high office at a time when Dutch Catholicism was beginning to collapse, with 95 percent of Catholics no longer going to Mass, vanishing vocations and the risk of the closure of up to 700 churches by the end of the decade.

In the last five years the reforms of Cardinal Eijk, a philosopher and a moral theologian, are turning things around, and there is now a trickle of vocations and the appearance of young and dedicated Catholics who accept “the whole faith.” Yet his successes may be limited if legal euthanasia is in fact a cause as well as a symptom of the secularization of Dutch society, a cultural malaise re-fashioning the very understanding of what a person is.

When I met Cardinal Eijk at Blackfriars, the Dominican house in Oxford, he was reflecting on the latest end-of-life innovation to be proposed by government ministers in his country – a new Bill which will effectively legalize assisted suicide on demand by prescription of lethal drugs to people who are simply tired of life and want to die.

This is not a new idea, the Cardinal said, but when it had been previously mooted there was a suggested age limit, initially of over 80 years. Now the government is not suggesting that any age limit be attached to the new measure.

The Cardinal is frustrated that virtually nothing can be done to halt it because euthanasia – a more direct killing of a patient by a doctor – is already legal. Euthanasia is the act of painlessly putting to death a person incapable of killing him or herself. Assisted suicide, instead, is the act of enabling a person to terminate his or her own life by providing them with the means of doing so, usually through a drug.

“We have already given away the most radical way of disposing of life (euthanasia) and it is difficult to say that less radical reforms of disposing of life (assisted suicide) are not permissible anymore,” the Cardinal said. “If we put the door ajar it will open in the end, and that is what we are seeing.”

Crossing the Rubicon

The Netherlands, guided by Health Minister Dr. Els Borst (who was murdered in 2014), became the first country since Nazi Germany to cross the euthanasia Rubicon in 2001. Belgium followed suit a year later, and in 2004 the Netherlands nationally enacted the Groningen Protocol, permitting the euthanasia of disabled infants. Luxembourg adopted a euthanasia framework in 2009.

Other countries have, in the meantime, been under huge pressure thanks to well-funded, well-organized and often celebrity-endorsed campaigns, to change their laws on euthanasia and assisted suicide. Six US states, including California and most recently Colorado, now permit assisted suicide, while 44 others at present are considering allowing it. In June 2016 Canada brought in both euthanasia and assisted suicide, and Switzerland and Germany in 2015 each relaxed prohibitions on assisted suicide.

Britain is swimming against the current by resisting enormous pressure to do the same. In 2015 the House of Commons voted by a huge majority to reject a Bill which would have legalized assisted suicide. A year earlier, the House of Lords, the upper chamber, threw out almost identical draft legislation.

Don’t go there

The proximity of Britain to the Netherlands may be a factor in the reluctance of Westminster to follow the Dutch experiment. Indeed, one of the most significant interventions in the Lords debate came from Professor Theo Boer, a former Dutch euthanasia regulator who told politicians that what had at first appeared as a good idea, even to him, had spiraled out of control. “Don’t go there,” he warned them.

It was sound advice because it is a fact that euthanasia and assisted suicide are almost impossible to contain in any jurisdiction where they have been legalized, and typically numbers of cases rise incrementally year on year and the boundaries are repeatedly pushed back.

Belgium, for instance, now has one of the most permissive euthanasia regimes in the world even though technically euthanasia remains an offence, with the law protecting doctors from prosecution only if they abide by carefully-set criteria.

Euthanasia was originally limited to adults who are suffering unbearably and who are able to give their consent, but three years ago it was also extended to “emancipated children.” The first teenager to qualify for the extended law died by lethal injection at the hands of euthanasia pioneer Dr. Wim Distelmans in 2016.

In spite of so-called safeguards, critics have argued that the law is interpreted so liberally that euthanasia is available on demand, with doctors giving lethal injections to disabled, demented and mentally ill patients alongside those dying from cancer. They include deaf twins Marc and Eddy Verbessem, 45, who were granted their wish to die in December 2012 after they learned they were likely to go blind, and Nancy Verhelst, a 44-year-old transsexual, who was killed by a lethal injection after her doctors botched a sex change operation.

The latest figures have revealed that numbers of doctor-assisted deaths have doubled within the last five years, soaring from 954 in 2010 to 2,021 in 2015.

Similarly, in the Netherlands safeguards were attached to the Bill to specify that patients could qualify for euthanasia only if they were suffering unbearably from an illness for which there was no cure. But unbearable suffering has turned out to be a very subjective judgment since the number of mental health patients killed by euthanasia has quadrupled in the last four years. The overall number of deaths by euthanasia in the Netherlands has also soared by 50 percent in the last five years, with 5,561 patients dying at the hands of their doctors in 2015.

False anthropology

According to Cardinal Eijk, 63, there is little prospect of the law on euthanasia or assisted suicide being reversed or even curtailed because it is underpinned by a false anthropology which has pervaded the whole of society.

The Church has always taught that body and soul constitute the human person, he explains, but contemporary thinking holds that man is just his mind and “the body is something secondary to the human person.”

The consequence of such ‘dualist’ ideology is that the human person has a profound right to dispose of his body by euthanasia and assisted suicide if he or she “arrives at the conclusion that it has lost all its instrumental value.”

“The problem is our present, hyper-individualistic culture in which the dignity of life is not viewed as a universal value for all human beings, but I myself am the only one who can judge the value of my own life; I am the only one who can see that,” said Cardinal Eijk.

“That is so radical in our country. We are so extremely individualistic that for many people they can’t conceive any more that there is a universal dignity. They are living in what Charles Taylor, the Canadian philosopher, called the culture of expressive individualism and authenticity – you have to be yourself, you have to choose your own religion, your philosophy of life, your set of values and distinguish yourself from others by your appearance.

“It is so rooted in the thinking of Dutch people that it is very difficult for them to conceive the possibility of a religion or a way of thinking that is shared by a community centered on God… people are not facing deeper questions, at least not openly, anymore. This makes it very difficult to discuss the universal value of life.”

New intolerance

So what does this mean for the future of the Church in lands where euthanasia and assisted suicide are legal? The signs do not look good. Rather than coexistence they point to a new intolerance. It is significant that in spring last year the Catholic St Augustine rest home in Diest, Belgium, was fined €6,000 after it stopped doctors from giving a lethal injection to Mariette Buntjens, a 74-year-old cancer sufferer who asked to die by euthanasia. Also, in the autumn, a federal court in Switzerland told a nursing home run by the Salvation Army in the canton of Neuchatel that it must provide assisted suicide to any resident who requested it or face the loss of state subsidies.

Neil Addison, director of the Liverpool-based Thomas More Legal Centre, said the two cases pointed to a “worrying” trend. “The law across Europe and indeed the West seems to be saying that organizations can’t have conscientious objection, but only individuals,” said Mr Addison, a Catholic.

“This is hitting at the very core of the religious hospitals and religious institutions because in essence it is saying that those organizations, if they provide services, can’t act in a religious way. That seems to be where the law is putting itself these days.”

He continued, “It is very worrying because it will have the effect of forcing religions back to do nothing else but offer worship and religious services, and will make the idea of religious charity very difficult.”

But even the right of individuals to object is under threat. In Canada five doctors have filed a legal challenge against the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario for its policy requiring medical professionals who refuse to participate in assisted suicide and abortion to refer those patients to other doctors. They and the Catholic bishops fear that the assisted suicide law, passed without any conscience provisions, could kill Catholic health care.

Future totalitarianism?

“Conscientious objection is under pressure,” Cardinal Eijk said, adding, “This development will continue. It will be ever more difficult for Christians to live their faith in present society.”

The Cardinal continued, “We know that in the past many Christians testified to their faith to the point where they were willing to accept jail and death. Let’s hope it will not get that far, but we have to be alert and we should try to empower our parliament members to prevent these developments. We have to defend the right to conscientious objection as much as possible.”

In the meantime, Cardinal Eijk will continue to quietly and steadily rebuild a small “but convinced” Dutch Church made up of Catholics who are clear about their faith, have active prayer lives and have a personal relationships with Jesus Christ. In view of the possible challenges which lie ahead he acknowledges it must also be a Church which is “willing to suffer.”