EVERY ONCE in a while I go to a small supermarket close to the Basilica of St. Anthony here in Padua to buy some little goodies to keep in my room in the friary: a few cans of sugar-free drink, some packets of oat-bran cookies, liquorice drops… in short, a few items that are generally harmless.

Some years ago, on walking back to the friary, I was stopped by a tramp whom I had been seeing for months begging around the Basilica. “What have you got in that bag? Any booze?” he asked. Surprised by his direct approach I opened the bag so he could see its contents. Quite understandably, he was disappointed by what he saw.

“Take anything you want,” I told him, and he removed a can of Diet Coke and a packet of cookies, perhaps more out of fear of appearing impolite than eager to have them; he then thanked me and went on his way.

From that day on I always gave him a can of Diet Coke or a similar drink along with a packet of cookies every time I crossed his path, and every time I saw him he would tell me a bit more about his life. I gradually came to know that he was Moroccan, that his name was Karim, that he had been in Italy for 10 years, and that unfortunately he was an alcoholic. He had been married once, with two kids, but his wife and children had left him because he was neither a good father nor a reliable husband. He had tried to give up his addiction several times, but alcohol always seemed to get the better of him.

One day he disappeared. I do not know if he returned to his country or, more likely, if he simply changed city. What I do know is that I miss this swarthy, unkempt, but good-hearted man.

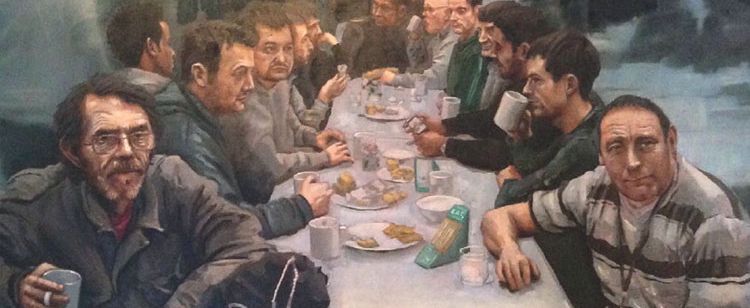

Karim came back to my mind a few days ago when I read in a British newspaper that Iain Campbell, artist-in-residence at Glasgow’s St. George’s Tron, Church of Scotland, had created a new version of the Last Supper featuring men in difficult financial or personal circumstances. Perhaps some may be scandalized when they see the apostles portrayed as a group of homeless people, but the message in the painting is quite clear: every supper these poor people have could be their last. The painting is, in fact, titled Our Last Supper (see picture). A closer look reveals that these people (whom the artist found among the 250 or so people being assisted by the charity’s centers at Glasgow) have been reproduced with blurry outlines.

There is a sense that there are some real, raw stories behind the faces in the painting. Moreover, Jesus is not recognizable in the painting. He could be any of the thirteen people seated at the table, in sharp contrast to paintings like Leonardo’s Last Supper in Milan where Jesus holds center stage. The author, Iain Campbell explains, “One thing that was at the back of my mind is something that Jesus said in the Gospels, ‘Whatever you do for the least of these my brethren you do for me’ so anyone of them could represent Jesus.”

There is enormous poverty in the world: lack of financial resources and lack of love. Tonight 795 million people in the world will go to bed with empty stomachs, and many, many more millions will go to bed with hungry hearts. They all need to experience God’s love and mercy.

Therefore during this Easter season let’s ask the Lord to arouse in us a sense of duty to bring God’s love and mercy to those less fortunate than ourselves, remembering that mercy is not just pity, nor is it a concern to help the needy without any personal involvement. Mercy is rather a personal concern which demands the giving of one’s soul and a giving from one’s possessions (and not just from one’s surplus).

As people who stand in daily need of God’s mercy and love, as people who pray with hands held out like a beggar’s bowl, we should in turn try to be kind, generous and merciful with others, because the measure we give will be the measure we receive (Luke 6:38).