Good Deeds

POPULAR Protestant preacher Charles Swindoll parodied Matthew 25: “I was hungry, and you formed a humanities club to discuss my hunger. I was imprisoned, and you crept off quietly to your chapel and prayed for my release. I was naked, and in your mind you debated the morality of my appearance. I was sick, and you knelt and thanked God for your [own] health. I was homeless, and you preached to me the spiritual shelter of the love of God. I was lonely, and you left me alone to pray for me. You seem so holy, so close to God. But I’m still very hungry and lonely, and cold.”

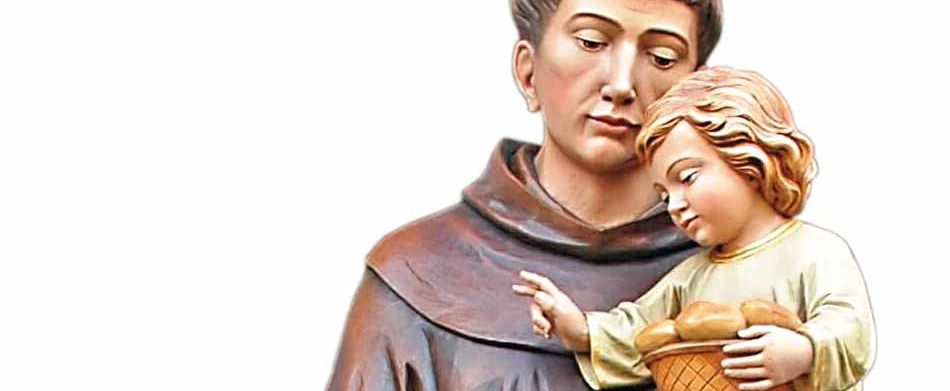

No one could accuse Saint Anthony of this lackluster, selfish way of deception regarding Jesus’ parable about serving him when we serve others. Stories of the Saint’s charity abound. His miraculous replenishing of spilled wine for a poor widow. His keeping a maid dry in a drenching rain when she brought food to the friary. His advocacy for debtors in Padua. His compassionate attention to a little girl with deformed feet. His unsuccessful intercession with a tyrant to release political prisoners, among them a young boy.

Alleviating suffering

The lay penitents who lived the Rule of 1221 were also true followers of Christ. Yes, they were intent on developing personal holiness. Holiness is built on faith and self sacrifice, both of which are part of their Rule’s penitential aspect. However, penitents also realized that holiness manifests itself in charity to neighbor. Praying and self discipline were important parts of the Rule of 1221, but they were not enough. Penitents had to do more than pray. They had to help alleviate suffering.

Charity was built into the Rule of 1221 for the laity. Those who were infirm, ill, or pregnant were excused from the fasting and abstinence enjoined by the Rule (Sections 6, 8, 10). The sick were exempt from praying the Divine Office (Section 13). Penitents were to be reconciled with their neighbors and to restore what belongs to others (Section 15). They were not to bear arms (Section 16), which forced them to maintain peace with all. At their monthly gatherings, they were to each give the treasurer a small sum, which was then distributed among the poor and sick (Section 20). At these gatherings, a religious was “to exhort them and strengthen them to persevere in their penance and in performing the works of mercy” (Section 21). These works included visiting the sick and burying the dead, both of which the Rule enjoins (Sections 22 and 23).

Life of the soul

Anthony’s sermon notes emphasize the importance of charity to acquiring spiritual perfection. Anthony calls charity “the life of the soul” (Sermons for Sundays and Festivals III, p. 135; translated by Paul Spilsbury; Edizioni Messaggero Padova). ‘Bread,’ which stands for every food, is charity, which should find its place with every food of good action. Let all be done in charity [1 Cor 16.14],” he writes. “Just as a table seems lacking without bread, so the other virtues are nothing without charity, because by charity alone are they perfected” (Sermons IV, p. 239).

What types of charity does Anthony recommend? “Almsgiving, which bears fruit among the needy” (Sermons I, p. 27) is paramount. So are “good deeds” which can take multiple forms. Anthony reminds his audience that the last judgment executes punishment for “good deeds not done” (Sermons III, p. 151). Hence, we are responsible for sins of omission as well as sins of commission.

Works of mercy

In his sermon notes about the rich man clad in purple and Lazarus, the poor man, covered with sores, at his gate [Luke 16: 19-31], Anthony stressed sins of omission. First, he brings out the contrast: “The first is rich, the other is a beggar. One is clothed in purple and fine linen, the other is full of sores. One feasts sumptuously every day, the other desired to be filled with the crumbs that fell from the rich man’s table, and no one did give him; moreover the dogs came and licked his sores.” (Sermons II, p. 10). Note how the rich man ignored the following corporal works of mercy, all of which were within his power to do:

- Feed the hungry

- Give drink to the thirsty

- Clothe the naked

- Shelter the homeless

- Visit the sick and imprisoned

By not showing mercy to Lazarus, the rich man is condemned to hell for sins of omission.

Anthony expands charity to include the spiritual works of mercy. Some of these are:

- Instruct the ignorant

- Advise the doubtful

- Correct sinners

- Be patient with those in error or who do wrong

- Forgive offenses

- Comfort the afflicted

Anthony teaches, “Your mercy, too, should be three-fold towards your neighbor. If he sins against you, forgive him. If he strays from the way of truth, instruct him. If he is hungry, feed him” (Sermons II, p. 81). This injunction includes both the spiritual and corporal works of mercy, and is a mirror of what early penitents actually did.

Small bees

Blessed Luchesio of Poggibonsi (died 1260) was the first recorded penitent to live the Rule of 1221. Saint Francis himself clothed Luchesio in penitential garb. Luchesio and his wife Buonadonna, also a penitent, sold their goods, lived poorly and simply, and fed and ministered to the poor.

Saint Margaret of Cortona (died 1297) was an early penitent who, after living a sinful life, had a profound conversion. Embracing penance, she went on to found a hospital for the sick, homeless, and impoverished. Then she began an order of sisters to care for them.

Saint Elizabeth of Hungary (died 1231) put aside her finery and used her dowry to build a hospital for the poor, then tended them herself.

These penitents, and many others, were the ones praised by Anthony when he likened them to “small bees.” “The small bees are the ones that do the most work… The fancy bees are the kind that do nothing. The small bees are penitents, who are small in their own eyes. They work hard and are always busy with something, lest the devil find their house empty and idle” (Sermons I, pp. 169-70).

For penitents, charity was the bedrock of their lives, for “God is charity” (Sermons II, p. 13).