Escaping Eritrea

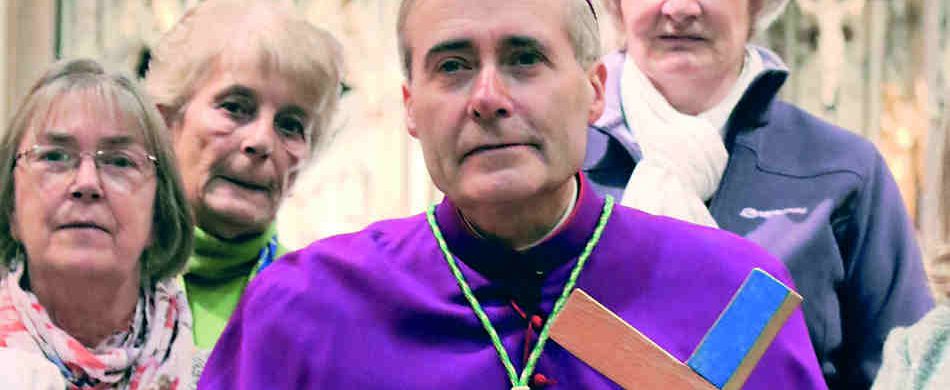

OVER THE last 12 months each of the cathedrals of England and Wales have been presented with their own ‘Lampedusa Cross.’ These are crucifixes carved by Francesco Tuccio, a carpenter on Lampedusa, from the wood of a boat upon which more than 300 refugees and migrants perished when it caught fire and sank close to the shore of the Italian island. Most of the dead had been fleeing Eritrea, a country on the Horn of Africa.

It would be a fair guess to say that many people in the congregations assembled to pray for the victims of such awful tragedies knew very little about Eritrea or, indeed, may not have heard of this nation at all. After all, it is a country so secretive and repressive that it has been dubbed the ‘North Korea of Africa’ by aid agencies and human rights groups deeply concerned about the plight of the people who live there. Last year, in fact, Eritrea was ranked last on the Reporters Without Borders World Press Freedom Index for the ninth year in succession.

Depleting population

What is evident, however, is that Eritrea is clearly a bad place, because its citizens are so keen to leave that there is now a million-strong Eritrean diaspora spanning the northern hemisphere. With 60,000 people departing each year, the nation is losing its population at a faster rate than any other African country.

Migrants not only risk their lives to traverse the Mediterranean in dangerous vessels from Libya but, in some cases, have crossed the Atlantic Ocean to reach Central America in the hope of finding a way into the safety of the United States.

Death by drowning constitutes just one risk undertaken in such journeys as there is a plethora of hazards waiting for Eritreans as soon as they leave their country. Some are snatched by modern-day slave traders preying along the smuggling routes into Sudan or Ethiopia. Others are taken hostage and then trafficked by Bedouins in the Sinai Desert and, according to US intelligence, they often become the victims of organ harvesting, rape, extortion, and torture.

In all, it is estimated that 90 percent of some 30,000 people trafficked in the Sinai between 2009 and 2013 were from Eritrea, but the dangers they are exposed to has done little to halt the flow of migrants.

Pastoral letter

The constant drain of vital youth, energy and talent from Eritrea is so grave that three years ago the country’s Catholic bishops issued a pastoral letter effectively begging people to stay in their country and appealing for those who have left to come home.

Called ‘Where is Your Brother?’ the letter also bravely jabbed the dictatorship of President Isaias Afewerki for failing to create the conditions to make people want to stay. “There is no need to emigrate if one lives in a decent country,” they said, adding that “there is no reason to search for a country of honey if you are in one.”

The problems in Eritrea pre-date the one-party rule of President Afewerki, however. In fact, Eritrea has been a leading refugee source country ever since the 1960s, when its 30-year war of independence from Ethiopia first broke out.

Previously, Eritrea had been an Italian colony between 1890 and 1941, when it was occupied by British forces following the Battle of Keren. After the Second World War, it was briefly administered by Britain as a United Nations trust territory until 1952, when the UN decided to make it a federal component of Ethiopia.

Within six years the Eritrean Liberation Front was formed and fighting erupted in 1962 when Ethiopia attempted to turn Eritrea into a province. About 150,000 Eritreans died in the fighting, some of them gassed or burned alive by napalm, before the war ended in 1991. A referendum of 1993 resulted in independence, but the exodus continued, with Eritreans migrating principally to Sudan, Yemen, Ethiopia, Egypt and Israel, before setting their sights further afield. Many wished to escape the paucity of basic rights or political freedom and educational and employment opportunities arising from a system which appeared to entrench grinding and perpetual poverty.

Later, others were desperate to avoid the mandatory military conscription that could compel men to serve in the armed forces until they are 50 years old, spelling effective enslavement in a lifetime of national service.

Religious persecution

In recent years Eritreans have been leaving their country to escape persecution on religious grounds too. Eritrea is a predominantly Sunni Muslim country but, with Christians making up 47 percent of the population, it also constitutionally recognises the Catholic, Coptic Orthodox and the Lutheran churches as religions and, on paper at least, it protects the rights of their adherents from discrimination.

In practice, life is made difficult for the official churches, while Evangelical and Pentecostal Christians are actively persecuted by the state, along with the followers of any other religion not recognised by law.

Catholics, who compromise just 5 percent of the population of 5.2 million, find activities severely curtailed, with charitable and social works almost completely stifled by restrictive laws, and attendance of Mass and other religious services often made difficult through the manipulation of the authorities.

The Catholic Church is just about clinging to its autonomy, having for now resisted attempts by the State to seize its 50 schools, 30 clinics and other institutions, although the compulsory national service has depleted its seminaries.

The larger Orthodox Church has suffered more grievously – not least because the Eritrean Orthodox Patriarch Abune Antonios has spent the last 10 years under house arrest after he refused to excommunicate 3,000 members of the Medhane Alem Orthodox Sunday School revival movement. He also had the temerity to demand the release of as many as 3,000 Christians held in jail on suspicion of treason.

Conditions are so bad in Eritrea generally that the human rights charity Open Doors has listed the country as the 10th worst in the world to be a Christian.

Indeed, human rights groups continue to document the harassment, persecution and deaths in custody of Christians in Eritrea, with reports of more than 100 arrests in the first six months of this year alone.

Brutal prisons

May was a particularly painful month. World Watch Monitor reported that 49 Evangelicals were arrested at a wedding feast outside Asmara, the capital, on May 21 just four days after more than 35 Christians were taken from their homes in Adi Quala by local police, and less than two weeks after the arrest of 10 other Christians in Ginda.

Once arrested, Christians can expect an extremely unpleasant time in custody, and some of them do not survive their ordeals. One charity, Christian Solidarity Worldwide, has listed at least 28 Christians who have died during their incarceration or shortly after release because of appalling mistreatment.

Some Christians have spoken of how they were tortured, virtually starved, made to carry out hard labour, and to live in filthy conditions with no medical care. Reports have described how in some cases religious prisoners were hung awkwardly from trees for several weeks without respite and until they could no longer move their arms and legs, meaning that they depended on other prisoners to feed and clean them. Other prisoners have been forced to walk barefoot on sharp rocks and thorns for an hour each day as a form of punishment while some were beaten with batons in an attempt to make them abjure their faith. There have been repeated reports of Christians being held in shipping containers – up to 50 at a time – which grow fiercely hot in the daytime, but turn freezing cold at night, though this is a punishment normally reserved for political prisoners.

Helen Berhane

One Christian who testified to such inhumane treatment is Helen Berhane, a musician who spent two-and-a-half years in prison for refusing to recant her Evangelical faith. She told Open Doors that the container in which she was imprisoned was “so cold during the night you would suffer hypothermia” and “so hot during the day that your skin would burn.” She says she was beaten and tortured regularly, but maintains that “every hit, every beating, and every blow to my body drew me closer to God.”

On one occasion she was battered with wooden batons after she was caught writing notes, including Scripture, from memory, with the aim of encouraging her fellow prisoners. She recalls that in the middle of the beating, she looked up at the guard hitting her and said to him, “I do not hate you. You are just carrying out an order, but you need to know that I’m carrying out an order too, and that order is not to renounce Jesus, so carry on…”

Constant warfare

The plight of Eritrean Christians, of course, is tied up to a certain degree with the insecure political situation of their country. Although Afewerki has served for decades as the country’s only President, he is nonetheless a strangely paranoid figure who believes that Eritrea is at constant threat of war.

This is largely because the border disputes with Ethiopia which led to the 1998-2000 war that claimed 80,000 lives have never been resolved to any satisfaction in spite of the repeated attempts at mediation by the international community and the presence of UN peacekeeping forces.

Over the last 15 years fighting has also broken out intermittently with neighbouring Djibouti over disputed border territories.

The result is a militarised, highly-restrictive and desperately poor society in which more money is spent on armaments than on agriculture – and at a time when the Horn of Africa is faced constantly with outbreaks of famine and severe drought. No wonder so many people want to get out.

Independent Church

There is not an awful lot that the Catholic Church can do to halt much of this, although there is huge pressure from the international community to change the situation.

Yet it is very interesting to note that Pope Francis in January 2015 established the ‘sui iuris,’ or self-governing, Eritrean Catholic Church from the ‘sui iuris’ Ethiopian Catholic Church.

On the one hand, the move could be seen as a practical acknowledgement of the real local difficulties of Church governance presented by the strife that exists between the two nations. But it is also possible to sense that the Holy Father is preparing the Catholic Church both for survival and for mission in a country which one day must surely emerge from the darkness of the present age.