Convening Agent

WITH THE countdown to the US presidential elections in November well and truly underway, there is one person who’ll be watching events unfold over the next nine months from a very particular perspective. Ken Hackett, from West Roxbury, Massachusetts, is the US ambassador to the Holy See, a post he was appointed to by President Barack Obama in the summer of 2013. Over the past two and a half years, he has helped to mastermind a major improvement in relations between his government and the leadership of the Catholic Church, culminating in the Pope’s visit to the White House and his address to a joint session of Congress last September.

From his elegant, wood-paneled office just off Rome’s central Via Veneto, Hackett and his staff represent America’s foreign policy to the Vatican and report back to Washington on what’s going on in Rome with regard to issues of common concern. At the start of his mandate, Hackett listed among his top priorities working for peace and the promotion of human rights, preventing human trafficking and highlighting the plight of refugees or Christian minorities being persecuted in different parts of the world. On a personal level, he said, he wanted to be a “convening agent, bringing people together,” in particular faith leaders whose vision and inspiration often “makes a real difference” on the ground.

All-time low

With no previous diplomatic experience, Hackett’s appointment may have come as a surprise to some, but in fact there were few people better qualified to take up that job at a time when relations between the Holy See and the Obama administration seemed at an all-time low. The week before he arrived in Rome, Hackett recalls with a wry smile, an estimated 100,000 people responded to Pope Francis’ call for a peace vigil and poured into St Peter’s Square to protest against proposed US-led bombings in Syria. The Pope himself attended the prayer vigil, reiterating that “violence and war are never the way to peace” and denouncing those “captivated by the idols of dominion and power” who “destroy God’s creation through war.” “Oh gee!” Hackett remembers thinking to himself, “this ain’t gonna be fun.” But he also acknowledges that, as a superpower, “we had certain responsibilities in the world which we exercised at times incorrectly – in some peoples’ judgment – and did things the Vatican just did not support” – most notably the 2003 invasion of Iraq, which Pope John Paul II so publicly opposed.

Jesuit education

While Hackett chooses his words carefully, both his Jesuit education and his four decades of working in development, poverty eradication and conflict prevention would suggest that he is easily in tune with the anti-war stance of popes past and present. His first exposure to the ideas of non-violent revolution go back to 1968, when he was volunteering with the Peace Corps in Ghana and sharing accommodation with a Czechoslovak priest who was following the dramatic events of the Prague Spring unfolding back in his homeland. After attending a Jesuit high school and university (Boston College), Hackett had a few job interviews with big companies like Ford and General Electric, but wasn’t, in his words, “overwhelmed by them, nor they by me.” Instead he headed out to West Africa to help build wells in one of the remotest parts of the country, sparking a passion that has driven his life and his work ever since.

Three years later he returned to the US and shortly afterwards got a job at the Africa office of Catholic Relief Services, rising swiftly to the rank of regional director. He spent 12 years based in New York and travelling tirelessly around Africa, dealing with emergencies like the Burundi genocide of 1972, the Sahel famine of the late 70s and the Ethiopia famine of the early 80s. It was exhausting and emotionally draining work, watching children die of hunger or communities torn apart by violence, and I asked the Ambassador if his faith played an important part in helping him cope with the day-to-day demands of his job. In a typically direct and honest reply, he admitted he didn’t have a catchy answer to that question, saying simply that he’d made the decision to “pedal as hard as I could pedal” and pray hard, knowing that as long as he did all he could, the rest was “in God’s hands.” Utterly dedicated to the people Catholic Relief Services was serving, he said he believed that “we had an obligation, as Christians, to do something, and we had a capacity, as Americans, to do something, so you put those two together...”

Exciting place

Following the 1983 to 1985 Ethiopia famine, however, both physically and mentally worn out, he asked for a transfer and was put in charge of Catholic Relief Services’ fundraising and relations with dioceses across the United States. It would only be a temporary respite from his work out in the field, but it was long enough for him to fall in love and marry a colleague, Joan, whom he had hired as Africa Regional Director. After the wedding in 1986, they asked to be assigned overseas and, with Joan already pregnant, were sent to the Philippines in the wake of another peaceful revolution which ousted long-time dictator Ferdinand Marcos. Their daughter, Jenny, was born there; Hackett describes it as “an exciting place,” with military coups, monster typhoons, earthquakes and the dramatic eruption of Mount Pinatubo in 1991, just some of the major emergencies that Catholic Relief Services was dealing with in those years.

Ken and Joan’s second child, Michael, was born in Kenya, and then in 1993 Hackett was named as Catholic Relief Services’ Executive Director, managing some 5,000 employees serving the poorest and most vulnerable people in over a hundred countries. He spent a decade in that job, before serving as President of the organization until his retirement in 2012. It was under his leadership that Catholic Relief Services responded to recovery efforts following the Rwanda genocide, the Bosnian and Kosovo emergencies, the Asian tsunami, and the Haiti earthquake. Equally notable during his tenure was Catholic Relief Services’ work to support people living with HIV-AIDS and the development of its vision based on integral human development for all – echoing a certain Argentinean Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio’s passion for social justice based on the rights of all people to ‘trabajo, techo y tierra’ (jobs, homes and land).

Sudden career change

Despite the diplomatic challenges awaiting Hackett on his arrival in the Eternal City, he says he had no real difficulties with the sudden career change from humanitarian chief to Vatican Ambassador. After four decades spent dealing with the Catholic Church at different levels in countries across the globe, he was on first name terms with many of the people holding key Curial posts, as well as with Vatican envoys, or nuncios, in different parts of the world. Having worked with the Pontifical Justice and Peace Council, as well as Cor Unum, the Vatican’s charitable arm, and with the Caritas Internationalis head office in Rome, he “knew the environment” and understood the “tensions between various factions,” as he diplomatically describes it. While many American bishops were voicing their opposition to the Obama administration, Hackett and his team set about showcasing for Vatican officials “everything that was good and positive” about US government policies. As the new Ambassador told journalist John Allen at the time, “I also believe that, when there are disagreements, we have to dialogue rather than throwing bricks at one another.”

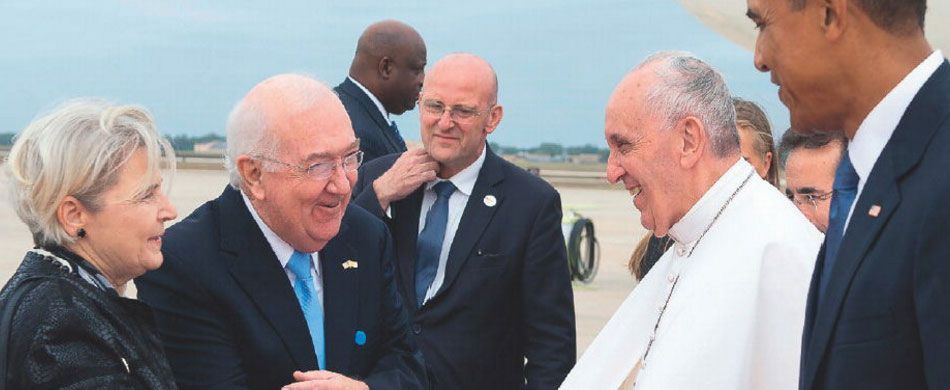

His tactics worked well and in January 2014 Secretary of State John Kerry made the first of three visits to the Vatican that year, striking up an easy relationship with his new Holy See counterpart, Cardinal Pietro Parolin. In March President Obama himself came to see the Pope, spending almost an hour in private conversation and inviting the Holy Father to come and visit the United States. Hackett points to a couple of photos of himself with the Pope and the President, both here in the Vatican and during the September 2015 papal visit to the US, though he notes with a grin that “my wife shows up more prominently than me!”

A man for others

Despite the obvious stresses of the job, Hackett invariably looks relaxed and smiling, sharing jokes as easily with parishioners at the English-speaking Caravita community church on a Sunday morning as with fellow diplomats and politicians on the most formal occasions. In 2014 he oversaw celebrations to mark the 30th anniversary of full diplomatic relations between the US and the Holy See, and in 2015 he managed his embassy’s move to a larger, more environmentally-friendly Chancery building, located on the same site as the US embassies to Italy and to the UN agencies in Rome.

I asked the Ambassador whether his Jesuit education gave him any insights that helped in his work of explaining a Jesuit pope to the people back home on Capitol Hill. He chuckles and says that back in his school days he was more interested in playing lacrosse than in the Jesuit concepts of ‘being a man for others’ or ‘finding God in all things’. At the same time, he admits that – perhaps more than other religious orders – the Jesuits “intellectually challenged you and forced you to think about deeper things,” at the same time as enjoying a full family, social or sporting life. Pope Francis, Hackett says, “is not a challenge, he’s an opportunity,” adding that “the whole concept of mercy to me makes tremendous sense and it’s what we should be about.”

Returning to the impending US elections later this year, Hackett suddenly looks more serious as he says, “I’ve been through lots of presidential changes, but this is something new.” Without mincing his words, he says that, as a representative of the President and of the nation, “some of the candidates that I see are an embarrassment to me, personally” and he adds it “would be a challenge” to represent a government “headed by some of the people I see in the debates.” But then he laughs again as he explains that all the US ambassadors are required by protocol to resign when the new president is elected, before being asked to stay on, or being replaced. Reminding me that he’s already retired once, Hackett insists that “my wife and I don’t intend to stay on forever! Let other younger, smarter people take the reins, we’ll stay only as long as we are useful.”