Art for God’s Sake

THE DRAWING of St Francis of Assisi by the American artist Daniel Mitsui is among the most original that can be imagined. Francis is considered by many Catholics to be among the most Christ-like of all of the saints, and is usually shown revealing his stigmata in total poverty. But here is a young Francis, clean-shaven and without the mystical wounds of the crucifixion. It is a scene from his life which followed his most profound conversion, when Christ spoke to him as he prayed in a neglected chapel in San Damiano.

He had taken literally the words of Jesus spoken from a crucifix, telling him to “go out and rebuild my house, for it is nearly falling down” and Mitsui captures the moment when St Francis is covered by the episcopal cloak of bishop Guido of Assisi after the saint publicly renounced his father's inheritance. The drawing is rich in symbolism, even down to the wildlife and the dense flora adorning the borders of the image, an allusion perhaps to the saint’s reverence for creation and patronage of animals.

Unusual style

What is more unusual, perhaps, is the style, which is redolent of the Gothic art of illuminated manuscripts, a common feature of much of Mitsui’s work.

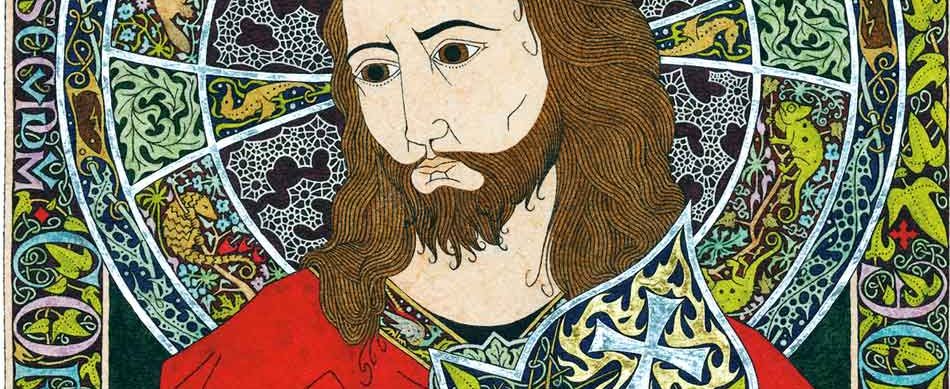

Take his depiction of the Sacred Heart, for instance, which represents a bold departure from the more sentimental depictions of 19th century artists, and harks even beyond the Baroque era of St Margaret Mary Alacoque to the 13th century inspirations of St Gertrude the Great, the German mystic who also nurtured a devotion to the heart of Jesus.

It is an illustration with a distinctive ‘Gothic feel’. A real yet simplified human heart forms a powerful central focus, then the picture extends in detail, with Christ’s halo richly decorated with such creatures as sea horses, pangolins, platypuses, lyrebirds and chameleons, which the artist has incorporated as symbols of universality.

The work has proved very popular as a contemporary version of a classic depiction of Jesus, with Mitsui asked to recreate it time and again, in different or in part colors, sometimes with just a crimson heart against black and white.

No cages

Gothic and Medieval art is where Mitsui, 38, is most at home. As a very young child he was captivated by its drama and aesthetic, and even by its recreation within non-religious stories like Eyvind Earle’s painted backgrounds to the Sleeping Beauty Disney cartoon, for example, or of Trina Schart Hyman’s depictions of St George and the Dragon.

It led him to study art in the early 2000s at Dartmouth College, New Hampshire, where he was guided, like his contemporaries, toward trends in gallery art, which he found generally uninspiring.

In 2004, soon after he was baptized a Catholic – the faith of his Polish-American mother – he began instead to perfect a style of his own, rooted in a tradition of Sacred Art, but not trapped by it, like “a cage or a limitation.”

Tradition & innovation

Mitsui explains that when an artist is attracted to a particular style, they might ask themselves such questions as: “Are there principles at work here? Are there rules of composition? Are there things that should and shouldn’t be done? Are there influences that I should seek out and ones that should be excluded?”

“Most artists go through this phase when they think about rules,” he continues. “It’s helpful and necessary, but if you never move past that you wind up with a very limited view. At some point you absorb the rules, you understand them well enough, and the question then is not ‘Do I like it?’ or ‘Is it following the rules?’ but rather the question is, ‘What makes it work?’”

“I don’t necessarily say I want to take traditional Medieval art and make it modern,” he adds, “but I am going to take it because I like it, and I am going to try to follow certain principles because they are there, but I am not going to stop myself from doing anything or drawing on any of the other influences that might make it better.”

Japanese influence

Moreover, sometimes novelty is part of the commission. A drawing ordered early in his professional career, for example, came from a priest asking him to depict St Michael the Archangel in the style of a Japanese woodblock print. The resulting work shows the archangel in the form of a Samurai warrior slaying a dragon with a sword.

“People really responded to it,” recalls Mitsui, whose father was a Japanese American. “They really loved that drawing and came to me asking me to do more.”

Part of his range of depictions of St Michael now features among the facemasks brought out by Mitsui in response to the coronavirus pandemic, at the suggestion of his eldest son. Other masks show Our Lady, and the miraculous Mass of St Gregory.

Vatican commission

It may be a paradox that by drawing on tradition Mitsui is proving that he can offer the world a style of religious art that is resoundingly fresh.

Mitsui is, in fact, so original that he was noticed internationally within just a year of turning professional in 2010. He was working from a studio at his home in Hobart, Indiana, when the Vatican commissioned him to illustrate a new edition of the Roman Pontifical, the liturgical book of rites and ceremonies usually performed by bishops.

He has since accepted a number of commissions from churches, including the intricate design of a carpet for a Catholic cathedral in Kentucky. Seminarians use his work to announce their ordinations, Catholics parents to celebrate the sacramental progress of their children. His art appears in altar cards, book plates and he has even brought out a series of coloring books.

He has recently embarked on a 14-year project to depict the Bible in 234 pictures, in ink on calfskin vellum, his favored medium, which he has called the “Summula Pictoria,” and which will present a great opportunity for him to draw the Old Testament. Because most of his commissions have been scenes from the Gospels or of patron saints, the chance to show more ancient figures was a rarity.

Bald prophet

Through his new project, however, Mitsui will bring 124 stories from the Old Testament to life, as well as summarize the life of Jesus Christ in 40 larger pictures. Others will show lives of the saints and the Blessed Virgin Mary, or scenes such as the Last Judgment.

He is not assembling the pictures in chronological order, but is painting them by commission, and those he has already completed are striking.

One is entitled The Repentance of Nineveh and it depicts Jonah as totally bald. “Our instinct nowadays is to say, ‘We are drawing a prophet, we are going to give him a big long beard,” explains Mitsui. “But one of the things I enjoy most in what I do is learning and analyzing older traditions and expressing them again. I really love finding these conventions and bringing them back,” he says.

“I discovered that it was commonly believed that Jonah’s experience inside the whale was almost a digestion, and when he was vomited out on the shore he had lost his clothing and his hair.

“The way that makes him look is almost like a new-born infant, and the implications of how you relate to him is of him being born again when he comes out of this thing that resembles the tomb. Smaller, thoughtful things like that I really find thrilling.”

Hildegarde of Bingen

The novelty and versatility of Mitsui reveal an artist at the height of his creativity, yet there is far more to come. He expects his biblical scenes to take him to 2031, and after that might come the project of his lifetime: drawing the visions of St Hildegarde of Bingen, one of his greatest inspirations. He recalls the thoughts of the 12th century mystic that people can recognize beauty because of the innate memory of Eden passed down to us by Adam and Eve. Despite the fact that we received our fallen nature from the first couple, a fragment of their memory of Eden remains innate within us. The purpose of art is to “elevate us towards that experience,” he says, adding, “I want to lift your mind and your soul and your spirit towards God.”

Daniel Mitsui lives in Chicago with his wife Michelle and their four children.