5 Classrooms

LIVING in huts made of wooden poles, mud, and leaves, the pygmy tribes of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) equatorial forests are on the lowest rung of the social ladder, according to Father Renzo Busana, Superior of the Dehonian Community in the Catholic parish of Babonde, and project manager of an initiative which aims to provide elementary education to pygmy children currently excluded from the school system. “If we look carefully at what happens in pygmy families, we can see that the number of children who are illiterate and who do not go to school is around 90 percent,” he says. “Pygmy children suffer from serious educational shortcomings due to a practical exclusion from school, as families lack the economic and social organisation requisites necessary to enrol their children in the system. Most of the pygmy population, and therefore their children, do not know how to read, write or calculate. Additionally, the vehicular language, Swahili, that allows communication between the different contiguous tribes, often remains unknown, leaving them isolated.”

Low life expectancy

Access to health care is also difficult: patients are responsible for all costs from consultation with a doctor to purchasing medicine, and from simple nursing services to surgical operations. “The pygmies benefit from many herbs and roots which they know have healing secrets,” says Father Renzo, “but they are unable to cope with more serious diseases that require specific treatment and medication due to lack of money and a fear of the hospital structure which they do not feel part of.” It is among the pygmies that the lowest life expectancy is found: around the age of 40.

“The right to education, enshrined in various international statutes and charters, is not applied well and punctually in many parts of the world,” says Father Renzo. “For the pygmy people, this right remains almost totally unfulfilled, relegating children to practical marginalisation.” He explains that the school system in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) faces many difficulties as a result of weak government planning in the face of rapid population growth. These difficulties include insufficient or a complete lack of infrastructure (schools, classrooms, and desks), insufficient staff training, and minimum wages guaranteed only for a small percentage of active teachers. “Given the many problems, parents take almost full responsibility for the schooling of their children. They look for a place and for teaching staff. They build classrooms, and thanks to their own contributions they provide teachers with a small wage which is often insufficient and de-motivating. After countless acrobatics and bureaucratic slowness, ‘parental schools’ are recognised by the state, and teachers begin to receive a salary from the Ministry of Education. The pygmy people remain far from this difficult development process. No one thinks of pygmy children, neither the state nor the parents, who have no experience of state educational mechanisms, lack the economic means, and are divided into small groups without social strength and initiative. Our project aims to respond to the essential need for all to receive a basic and sufficient education without racial or ethnic discrimination.”

Raising awareness

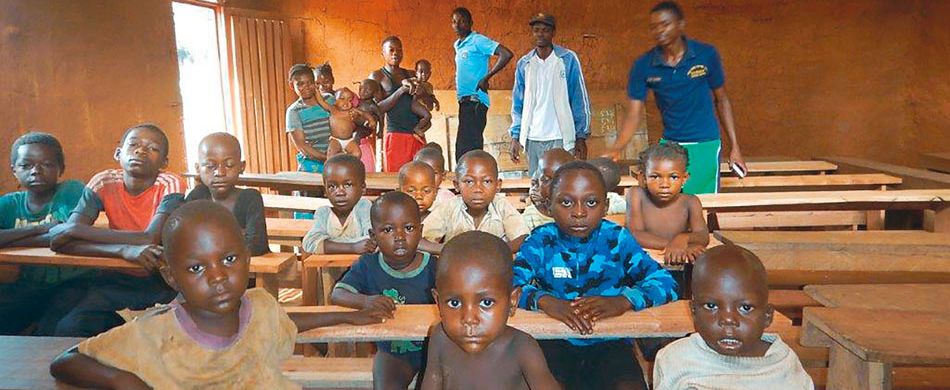

The Catholic mission, governed by the Priests of the Sacred Heart of Jesus (Dehonians), is based in Babonde, and around 44 villages are entrusted to it for pastoral care, human development and promotional activities. The population is mainly from the Walika tribe (Bantu), but with a very strong minority presence of pygmy tribes scattered across numerous encampments. Over the last ten years, the parish has focused on raising awareness of parents to the schooling of their children, seeing this as key to their emancipation. Some classrooms have been built using local materials near to pygmy encampments, allowing easy access for children. Teachers have been encouraged financially. “The classes for the pygmy children have sometimes seen a number of Bantu children also attend,” adds Father Renzo. “They have taken advantage of these schools due to a lack of state schools nearby. This has been favourable for integration and mutual familiarisation of the two groups.” The schools provide one or two years of preparation for attendance at the state school. Once prepared, the pygmy children, along with their Bantu peers, continue schooling up to the sixth grade.

14,500 Euros

Father Renzo explains that the current project identified five pygmy encampments from the approximately sixty in the area, Bovoboli, Bavazolya, Gbunzunzu, Ndokajuu and Bovotubu, based on certain criteria: “In previous years there had already been some schooling, and sensitivity and expectation on the part of the parents had become evident. The camps are close to the main communication route, and there is a state school in the vicinity which will allow the children to continue their schooling.” Local authorities made some land available to construct the classrooms and guaranteed their safe keeping. Parents and the local community – both pygmy and Bantu – agreed to collaborate with manual work and to provide food to the skilled workers on site. They also agreed to build and plaster perimeter walls after the classrooms had been built. The total costs to build the five classrooms was €15,800. After a local contribution of €350, and €950 from the local religious community, St Anthony’s Charities approved a grant of €14,500 to cover the remaining costs.

Mungu asifiwe

The project began in November 2017 with the distribution of scholastic materials and financial help to the as the school year had already begun. It was the rainy season, so work on building the new classrooms was scheduled for January 2018. However, due to transportation problems of the necessary materials, work did not begin until March. A considerable saving was made on roofing materials, so part of the savings were used to buy uniforms for the children as often they were abandoning studies due to a lack of appropriate clothing, or any at all. By the end of May, two of the classrooms had been built, and materials for two of the remaining three delivered to site. Finding material for the final classroom proved difficult due to accessibility and distance problems. By the end of July 2018, at the end of the school year, all classrooms had been completed using insect resistant wood and corrugated metal roofs. All classrooms were equipped with desks, blackboards and doors.

At its conclusion, Father Renzo reported on the state of the project, “We can list with full satisfaction the objectives achieved: schooling and literacy of about 120 boys and girls, construction and equipment of five classrooms, provision of teaching materials including uniforms, economic support for animators and teachers dedicated to schooling and literacy.” However, it was not all positive: the continuity of the project depends to a large extent on the state fulfilling its duties by recognising new schools and financing them economically. “Once again this year, we bitterly noted the failure and disinterest of government authorities in taking charge of the service and work of teachers who continue to suffer from a lack of salary and have to settle for a small, insufficient ‘award’ that parents manage to put together. In our last meeting, however, satisfaction in the performance of the school year was manifested by everyone with great joy.”

“We offer a very heartfelt thanks to St Anthony’s Charities and the readers of the Messenger of Saint Anthony for their positive response to our project,” concludes Father Renzo. “The whole council of the pygmy pastoral ministry and the teachers and directors thank you and say with joy ‘Mungu asifiwe’ (God be praised) – in His great Providence.”